The story of Sail Britain’s NW Scotland Geology Expedition. Guest post by Harriet and Rob Fraser of somewhere-nowhere

August 20. There’s autumn on the wind and gold on the water. The sky’s grey morning has cleared to blue and I have slowed to the leisure of 2 knots and sunshine, floating on a velvet sea. There’s no conversation among the eight crew. We are each drifting with the black-blue water as it catches the late afternoon light and laps with a soft, slow rhythm against the boat. And then we gasp collectively: a pair of porpoises to port, showing themselves in moments, in unison, black and glistening, rising and falling, rising and falling, rising and falling.

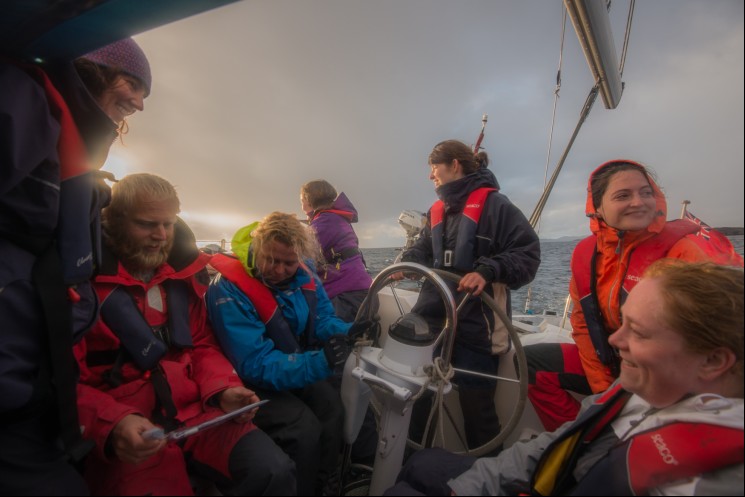

Day one and my first experience of sailing has come to this: leisure, smiles, sunshine and ease. I’ve taken a turn at the helm of the 38-foot yacht, Alcuin, in a light breeze, and felt, for the first time, a sense of being part of a continuum that connects wind, water and boat, brings together water, air and muscle, demands a specific body-awareness, and, when everything works well, feels utterly joyful, something like flying and running and swimming and singing, all wrapped up into one.

We’re en route to the Summer Isles, having sailed out of Loch Broom on a trip that’s bringing together rocks and sea in an unusual way. The next ten days of sailing will take us on an exploration of Scotland’s northwest coast, past the Torridonian giants of Stac Pollaidh, Suilven and Quinag, and into and out of lochs with sheltered bays for quiet nights. The scenery here is not just jaw-droppingly beautiful, it’s also one of the richest landscapes, in geological terms, on the planet.

Even before we’ve left Loch Broom, just a couple of hours’ sailing from Ullapool, I’m being treated to a narrative of the land’s long, deep history. One of the three geologists on board, Anna, points out a raised beach to starboard: an area of flat, grassed land several metres above the current beach. It emerged, she tells me, a ‘mere’ fifteen thousand years ago when the land breathed a sigh of relief at the lifting of weight, a tremendously heavy glacier melting, sliding into water, and passing on. Behind the raised beach the line of white is sandstone deposited 500 million years ago along the edges of an ocean that used to be between Scotland and England. This ocean closed when huge continents pushed up against one another, tilting the sandstone and forcing one-million-year-old metamorphic rock up above it: an incident that’s marked in the Moine Thrust (we’re looking at just one part of this 190km-long Thrust, which runs from Loch Eribol to the Isle of Skye). In among the mix there is grey, mottled gneiss, which has been here for three thousand million years. This text of rock tells a story of time that’s, to me, incomprehensibly old. But as Anna talks me through it, the solid land begins to seem almost as dynamic as the sea. I imagine the unheard sound of mountains moving, a million winters of ice, and toy with the idea of making a time-lapse on a geological scale, shooting one frame every thousand years …

.. then it’s time to tack, and the crew gets ready. Oliver calls Ready About, and waits for the replies – Ready Starboard, Ready Port. It’s time to bring the jib (front) sail from one side to the other, tightening the ropes on the port side, and loosening them on starboard. All hands are on deck and the boat begins to turn. Oliver calls Helm’s a Lee, and, as we catch the new course, shouts Lee Ho. Alongside geological insights, I’m beginning to learn words from the extensive lexicon of sailing. Over the coming week I learn more, and discover just how many of them have found their way into everyday vocabulary. While, quite literally, learning the ropes, I’m getting to know the rest of the crew, staying on the right side of nausea (or on an even keel) and discovering just what it’s like to sail.

Rob and I are here as part of Sail Britain’s Coastline project, a series of trips around the UK coast bringing scientists and artists together to share knowledge and inspiration while sailing. From my point of view, this is a great recipe for new experiences, learning, and new friendships – but perhaps the biggest lure to come was a wish to go beyond my known limits and give myself a chance to deepen my connection with an environment that I have only ever encountered from its edges. I have to be honest at having some anxiety at the possibility of feeling horribly sick/cold/wet, but this was not as strong as my excitement and my urge to explore. For Rob, the decision was slower – having sailed plenty of times in the past (he was photographer for the Tall Ships race for ten years when it was sponsored by Cutty Sark Whisky) he has haunting memories of how awful it is to feel sea sick. But in the end his curiosity won out. We decided to put ourselves all at sea.

For this trip, skipper Sail Britain director Oliver Beardon has gathered a crew of artists and geologists. The geologists – Anna Bird, Eleni Wood and Stacy Philips – have an effervescent passion for rocks, and their knowledge gives everyone on the boat an entirely new perspective on land. They’re filming a documentary and researching rock types that, for their great age, are matched only in one region of the Himalayas. Fine artist Emma Harry is also on board: she makes exquisite drawings, and her art practice is all about rocks. We’re here to bring photography and poetry into the mix. The eighth crew member is first mate Thea whose knowledge of ropes and patient teaching helps me learn quickly enough to tie a bowline to an anchor-marking buoy at the end of the first day. (I feel extremely chuffed that the buoy is still there in the morning.)

For a couple of days, off the northwest coast, we didn’t see any other boat. The blue of the sea stretched for miles and we were joined only by birds, among them gannets, skuas, fulmars, guillemots and razorbills. All of us on the boat were delighted and excited to sail alongside these companions, witnessing their elegance, grace and ease in their own elements of air and water. And to sail with dolphins racing, flipping and gliding effortlessly, so close we could look them in the eyes, almost touch them – that’s a beautiful, joyous experience that can never be done justice on any film, however good.

Out here, on the blueblack backs of water mountains, we are the only boat. All around us is a moving sea where a clash of wind and tide, coupled with a poor tack, can put you in irons, they say. There are no irons out here. Only wind and water and boat with eight people afloat out of our element where we could sink like stones. But we don’t, of course – we fly, wind caught well, waves in our favour, for a time we are almost as slick as the dolphins that come to play, dip beneath us, roll, leap, click and look, then leave in fluid flight, at home in what we call wild.

Sitting astride the cockpit coaming as the boat cuts through the water at 45 degrees, gazing out to the blue horizon in the west, and across to the distant, gnarled coast, with nothing but sea-loving creatures for company and more than 100 metres of liquid depth beneath me, I can imagine why, not so long ago, people thought the ocean provided an endless resource and could never be depleted. Of course that’s not the case, and the world’s focus is now well and truly on the harm that humans are causing to the oceans, with dramatic decline in sea life due to over-fishing and habitat disruption, and an alarming level of plastic pollution. After swimming in what felt like the pristine waters of Loch Shark, I was brought close to tears when I came across a plastic strewn across a beach on a neighbouring loch. Our forays onto land until now had brought us to inlets covered with shells and sand, fascinating rocks, incredible views, and the mesmerising push and pull of seaweeds along the littoral line. This beach was different: baskets, crates, bottles, lids, twine, tags, pegs, funnels, nets and shattered plastic remains swamped the washed up seaweed. We weren’t in a position to remove the huge quantity washed up here, and felt powerless and sullen. The waste included chunks of polystyrene that have merged into the land, covered now with mosses and heathers. These modern day anthropogenic rocks will gradually release pieces of themselves into the earth, the sea, and into the guts of unwitting creatures.

As he’s been skirting the coast this summer, Oliver has been taking samples of sea water to be checked for plastic. Eleni and Stacy have also brought kits with them, and will be sending samples back to their university for analysis. It’s the plastic that can’t be seen with the naked eye that’s of particular interest to researchers. However upsetting the discoveries may be, the more that is known, the more likely effective changes will be made – driven by policy and raised public awareness – in the manufacture of everything from clothes to toiletries and the way humans around the world use, re-use and discard plastic, and find alternative materials. When we pull in the net that’s been trailing alongside the boat it seems there’s only seaweed in there. But Oliver and I look closer: in among the seaweed there’s a tiny filament of purple. I wonder about the plastics littering the sea’s bed, and geological lines of the future showing bright yellows, reds and greens between earth-coloured layers of stone.

Thinking about time

a week that’s mostly about sailing

isn’t really enough time

to get my head around time

when time is measured in so many ways

three thousand million years in grey lichened gneiss

ten thousand years held in an inch of sandstone

or a day captured in a metre

geology stretches time, shrinks time

counts a wide and deep time

in signatures of long-gone rivers

lines of pressure, melts and folds

time in rocks buffering the sea’s slosh

beside our measured speed of wind and knots

the time of stomach’s emptying

the time of tides

and the time it takes to settle

in a new element

in a small floating space

held between a rolling hitch, a bowline

and an unfurled jib

Over the course of the week, our time at anchor is spent largely doing necessary chores – preparing food, cooking, and washing up. But we do have enough time to enjoy leisurely meals, warming whiskeys, and many cups of tea, and we get to know one another in a special way that’s brought on my living in such close quarters. And we spend some time on land to get a close look at rocks. When we’re not sailing – and sometimes when we are – we pull out sea charts and geological maps, draw and paint, write, line rocks up for identification, and even make lego versions of ourselves (thanks to Stacy’s exhaustive collection of nautical pieces).

When the boat’s in motion we spend hours and hours on deck, and often we share the space in silence. I find myself drifting into a reverie that’s wordless: a gentle, open mental state that almost allows the energy of the sea to wash through me. I soak it in, and relish this new sense of passing through a space that is so vast, and so deep, and bulges with paradoxes. The sea’s a constant, yet it is never the same, shifting moods and wearing different masks from hour to hour. It feels solid, and buoyant, yet is liquid and would swallow you up in an instant. It looks empty, but is full. Run your hands through it and it feels light, but is incredibly heavy (just imagine 100 metres of water on your head). It can lull you into comfort, or give you the worst kind of sickness. It seems soft, but can wear away the hardest of rocks. It’s something you can get to know, yet never know, trust and distrust at the same time.

One week’s not long, but is long enough to leave me feeling slightly more connected with the watery element that covers most of this planet. I’ll be working now to transform notes into poems, and Rob is developing and printing his black and white images, which we’ll share in the next blog. We both know that our sea time is not done: we’re already planning to return.

September 5: Notes made back at home

I re root

myself on solid familiar land by walking through green, tracing the old

ways the lead from my back door to the river, passing between high

hedges flush with summer growth, the last of the blackberries over-ripe

and fly-busy, and the first oak leaves turning gold. In the garden we

mow the grass that’s grown to shin height, fill three barrows with

windfalls, gather nearly seven pounds of plums and dig up potatoes for

tea. The sea is nowhere to be seen, heard or felt – except in my newly

made memories and my body’s awakened senses. There’s something there

still though. Just as the sea’s waves do not die down until long after

the wind of a storm has passed, the presence of the sea still

reverberates in my cells. And there’s a call, I think, to go back …

I can’t help recalling the words of John Masefield:

“I must down to the sea again, to the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song and the white sail’s shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea’s face, and a grey dawn breaking…”

More info:

Emma Harry’s beautiful work can be seen at her website here.

We met Oliver at the Royal Geographical Society’s Explore weekend. This annual event is packed full of talks, presentations, workshops and opportunities to gain inspiration on any element of exploration and travel that involves learning more and reflecting on the natural world. This year’s event in London runs from 9-11 November.

Eleni, Stacy and Anna are creating a documentary with a geology focus, in association with the Open University and Hull University: we’ll share this when it’s done. Eleni and Stacy also run Fieldwork Diaries, a podcast sharing interviews with geology researchers around the world.